Santeria/Afro-Cuban Religion

When African slaves were brought to Cuba to work on the sugar plantations, they brought their religious beliefs with them. Most of the slave population came from four major groups: Bantu from the Congo, Yoruba and later Igbo from Nigeria, and the Arara from Dahomey. The African religious pantheons all have a principal god plus other minor deities (orishas), and the Cuban transplants soon noted similarities with the Christian hierarchy of supreme being and saints as conversion was forced upon them in Cuba. This led to syncretism wherein, for example, the Catholic San Lazaro, resurrected from the dead by Christ, became connected with the orisha Babalú Ayé, ruler of contagious diseases. Thus, during the period of slavery, native religious practices could easily be camouflaged under the guise of Christianity. Contemporary Afro-Cuban religion has three main practices: Santeria, Palo Monte, and Abakuá. The first two are largely syncretized with Catholicism, African elements outweighing the Catholic ones, while Abakuá is a secret society for men.

I read several articles on Afro-Cuban religions before the trip, as well as some collections of myths and stories about the various orishas. What struck me was the similarities with creation myths and folktales from other cultures, whether Greco-Roman, Celtic, Polynesian, or Chinese: the roles of the deities take familiar paths, and the gods seem to behave (often badly) in much the same way. In Santeria, as with other religious pantheons, we have a god of war (Changó) and a goddess of love (Oshún), a mother figure (Yemayá), a trickster (Elegguá), a divine hunter (Ochosi), a healer (Babalú Ayé), etc. The syncretism is a little more baffling but fascinating, my favorite being the Changó-Santa Barbara connection: the axe-bearing warrior (also a great dancer and womanizer) conflated with a third-century virgin martyr who was beheaded by her own father for converting to Christianity. OK, yeah, she carries a sword (the emblem of her martyrdom), and is the patron saint of artillerymen, military engineers, miners and others who work with explosives because of her association with lightning (a lightning strike killed her father, in retribution). But she was not a warrior, nor was she a man; Santeria lore explains this cross-sex connection with a story about Changó having to disguise himself as a woman to avoid some enemies. (Just like a guy!)

I read several articles on Afro-Cuban religions before the trip, as well as some collections of myths and stories about the various orishas. What struck me was the similarities with creation myths and folktales from other cultures, whether Greco-Roman, Celtic, Polynesian, or Chinese: the roles of the deities take familiar paths, and the gods seem to behave (often badly) in much the same way. In Santeria, as with other religious pantheons, we have a god of war (Changó) and a goddess of love (Oshún), a mother figure (Yemayá), a trickster (Elegguá), a divine hunter (Ochosi), a healer (Babalú Ayé), etc. The syncretism is a little more baffling but fascinating, my favorite being the Changó-Santa Barbara connection: the axe-bearing warrior (also a great dancer and womanizer) conflated with a third-century virgin martyr who was beheaded by her own father for converting to Christianity. OK, yeah, she carries a sword (the emblem of her martyrdom), and is the patron saint of artillerymen, military engineers, miners and others who work with explosives because of her association with lightning (a lightning strike killed her father, in retribution). But she was not a warrior, nor was she a man; Santeria lore explains this cross-sex connection with a story about Changó having to disguise himself as a woman to avoid some enemies. (Just like a guy!)

Our group was very fortunate to attend a lecture by Natalia Bolivar, the leading world scholar of Afro-Cuban religions, who gave us a history of these religious practices and an outline of the tenets and pantheon of the leading sects. Professor Bolivar also kindly donated copies of the English translation of her book Santa Barbara-Changó, and joined us for a book-signing session and our farewell dinner. Professor Bolivar was both erudite and accessible, and her depth of knowledge of and experience with Afro-Cuban religions were a great help to us in appreciating the visits we made and performances we attended during the trip.

The first of these was a visit to Yoruba babalawo Octavio Rodriguez at his home in Central Havana, where he explained the use of the sacred batá drums and blessed our visit with a demonstration performance also featuring his wife and son. A respected community leader, Octavio provides advice and assistance to anyone in the neighborhood, and participates in one of two national councils of babalawo in Cuba to determine the annual proclamation of predictions and advice, "Letra del año," for the new year. As his "day job" Octovio performs with several different Havana musical ensembles.

The first of these was a visit to Yoruba babalawo Octavio Rodriguez at his home in Central Havana, where he explained the use of the sacred batá drums and blessed our visit with a demonstration performance also featuring his wife and son. A respected community leader, Octavio provides advice and assistance to anyone in the neighborhood, and participates in one of two national councils of babalawo in Cuba to determine the annual proclamation of predictions and advice, "Letra del año," for the new year. As his "day job" Octovio performs with several different Havana musical ensembles.

Religious music is an important part of Afro-Cuban ritual, with specific chants, rhythms and instruments; conversely, religious music has helped form the basis of Afro-Cuban popular music styles, such as son which fuses Spanish guitar and lyrical traditions with African percussion and rhythms. In Havana, we had our first taste of traditional Afro-Cuban music, at the Palacio de la Rumba in the Vedado district of Havana, a venue off the tourist beat with energetic performances and cheap drinks. (Actually, drinks are pretty cheap anywhere in Cuba...)

Religious music is an important part of Afro-Cuban ritual, with specific chants, rhythms and instruments; conversely, religious music has helped form the basis of Afro-Cuban popular music styles, such as son which fuses Spanish guitar and lyrical traditions with African percussion and rhythms. In Havana, we had our first taste of traditional Afro-Cuban music, at the Palacio de la Rumba in the Vedado district of Havana, a venue off the tourist beat with energetic performances and cheap drinks. (Actually, drinks are pretty cheap anywhere in Cuba...)

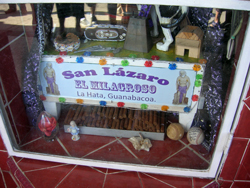

We also went to the La Hata neighborhood of Guanabacoa, an area on the outskirts of Havana that is the center of Santeria culture, to pay a visit to Enrique Hernández Armenteros (aka Enriquito de La Hata), founder of the Hijos of San Lazaro and one of the most prominent babalawo in Cuba. Afterwards we had a tour of the Guanabacoa Historical Museum, boasting extensive displays of artifacts from all of the Afro-Cuban religions (as well as one of the earliest American cars, a Cadillac, brought into Cuba!).

We also went to the La Hata neighborhood of Guanabacoa, an area on the outskirts of Havana that is the center of Santeria culture, to pay a visit to Enrique Hernández Armenteros (aka Enriquito de La Hata), founder of the Hijos of San Lazaro and one of the most prominent babalawo in Cuba. Afterwards we had a tour of the Guanabacoa Historical Museum, boasting extensive displays of artifacts from all of the Afro-Cuban religions (as well as one of the earliest American cars, a Cadillac, brought into Cuba!).

In Matanzas, one of the most important centers for Afro-Cuban religion, we visited the La Salsa Que Te Mueve for a performance by one of Cuba's most acclaimed folklore groups, Afrocuba de Matanzas. My favorite of all our Santeria-infused musical experiences, however, was at the center for the Hijos de Santa Barbara in the small town of Palmira, outside Cienfuegos. This is one of the oldest communities in Cuba, the building (and the rather gaudy statue of Saint Barbara) having been donated in the 19th century by the former master of one of the founders, in thanks for assistance she had given him. The intensity and energy of these performers left a lasting impression, as the dancers became totally immersed in their roles to allow communication with their orisha counterparts. Elegguá, the consumate trickster, stole our hats and scarves, exchanged bits of clothing with us and the other performers, and enticed us all to join them in the dance.

In Matanzas, one of the most important centers for Afro-Cuban religion, we visited the La Salsa Que Te Mueve for a performance by one of Cuba's most acclaimed folklore groups, Afrocuba de Matanzas. My favorite of all our Santeria-infused musical experiences, however, was at the center for the Hijos de Santa Barbara in the small town of Palmira, outside Cienfuegos. This is one of the oldest communities in Cuba, the building (and the rather gaudy statue of Saint Barbara) having been donated in the 19th century by the former master of one of the founders, in thanks for assistance she had given him. The intensity and energy of these performers left a lasting impression, as the dancers became totally immersed in their roles to allow communication with their orisha counterparts. Elegguá, the consumate trickster, stole our hats and scarves, exchanged bits of clothing with us and the other performers, and enticed us all to join them in the dance.

Return to Cuba 2012-2013 Index