Backstopping for the Intoxicators

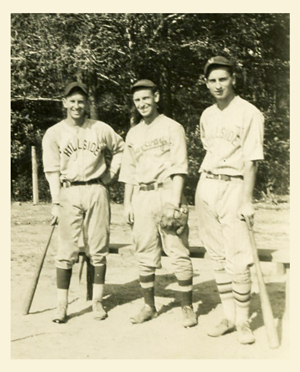

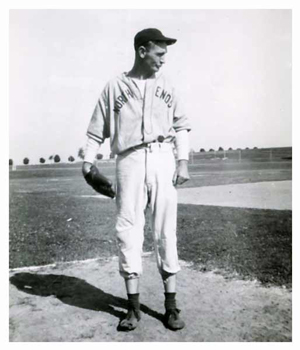

I grew up on baseball. My father and his three brothers were all serious ballplayers: Dad on semi-pro teams all around New Jersey, Uncle John on company semi-pro teams (he played with Joe Medwick for Esso, and, according to family lore, also somewhere with Stan Musial), and Uncle Art in the minors for the Newark Bears (more family lore claims that Art was scouted by the Yankees). One of the two pieces of advice my mother gave me was to not get married during the World Series, a mistake she made. (The other advice was not to date short boys.) The other Farrell boys were all Yankee fans but my father, being the black sheep of the family, brought his kids up to root for the Brooklyn Bums. Those were heady days for the Dodgers—Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Sandy Koufax, Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Carl Furillo, Gil Hodges—their youthful faces still fresh in my memory from years of flipping baseball cards with my brothers. The Dodgers and Giants both moved to California in 1958, ripping holes in the hearts of National League fans throughout NJ (and NY) that the early Mets were as unable to fill as they were to win games. But that was long ago. My family made a pilgrimage to Cooperstown in '59, saw Zack Wheat inducted and watched a game at Doubleday Field (Kansas City Athletics vs. Pittsburgh Pirates). I saw Sandy Koufax pitch once, in the mid '60s, against the Mets (a double-header, Johnny Podres took the mound in the other match). He was impressive, both on the field and off: I chose Koufax for a "Man of the Year" essay in my high school Modern History class. (Got a B+—Mr. Jayson was not a big baseball fan.)

My Uncle John had a farm and our annual 4th of July family picnic was one day-long softball game interrupted by burgers and tractor rides. My dad inaugurated a Little League-esque program in our town, and I spent most of those summers wedged into our Ford Ranch Wagon with 15 squirmy pre-adolescent ballplayers and a bag of bats, balls, and other gear. My first encounter with some of the less, uh, visible baseball accoutrements was finding my brother Rocky's cup (he caught and played second base) in the bathroom. My father told me it was a nose guard.

My Uncle John had a farm and our annual 4th of July family picnic was one day-long softball game interrupted by burgers and tractor rides. My dad inaugurated a Little League-esque program in our town, and I spent most of those summers wedged into our Ford Ranch Wagon with 15 squirmy pre-adolescent ballplayers and a bag of bats, balls, and other gear. My first encounter with some of the less, uh, visible baseball accoutrements was finding my brother Rocky's cup (he caught and played second base) in the bathroom. My father told me it was a nose guard.

My mother and a few other baseball moms inaugurated the first Junior Baseball cheerleading squad, for the Giants (the team my dad coached). The ladies made our uniforms and taught us some moves. I'm not sure where this came from; my mom played basketball in high school (even though she was under 4 foot 10) and as far as I know was never a cheerleader. Maybe my girlfriends and I whined that we couldn't play; I only got to pitch to my brother (in the street—we were dead end kids) on the rare occasions he couldn't find anybody else to practice with.

After I left New Jersey, I drifted away from baseball, living in a bunch of places without major league teams or much of a baseball culture (football rules in the Big Ten, basketball reigns in Indiana). In Hawaii, the best way to watch the Triple A Hawaii Islanders was on ten cent beer night, when multiple draughts of cheap Primo deadened the dual blows of seriously bad playing and stale manapua.

Baseball, however, draws one back in. It's stable, it's pure, it's universal. As W.P. Kinsella points out in his introduction to the short story collection Baseball Fantastic, "Baseball ... knows no time limits. On the true baseball field, the foul lines divulge forever, eventually ... taking in most, or all of the universe." Unlike other sports, baseball has mythic qualities, something that has always fascinated me. Baseball has inspired poems, novels, and films in ways that transcend its identity as a "mere" game, lifting it to the status of potent metaphor for life, the universe, karmic struggle, spiritual redemption—take your pick. I even wrote a conference paper on this and got it published in Elysian Fields Quarterly (a feat that probably impressed my baseball-playing brother more than anything else I've ever done).

Baseball, however, draws one back in. It's stable, it's pure, it's universal. As W.P. Kinsella points out in his introduction to the short story collection Baseball Fantastic, "Baseball ... knows no time limits. On the true baseball field, the foul lines divulge forever, eventually ... taking in most, or all of the universe." Unlike other sports, baseball has mythic qualities, something that has always fascinated me. Baseball has inspired poems, novels, and films in ways that transcend its identity as a "mere" game, lifting it to the status of potent metaphor for life, the universe, karmic struggle, spiritual redemption—take your pick. I even wrote a conference paper on this and got it published in Elysian Fields Quarterly (a feat that probably impressed my baseball-playing brother more than anything else I've ever done).

Although I was chosen South Plainfield's Miss Junior Baseball 1962 (I have a trophy, honest!) I didn't actually play on a team until I moved to Boulder, Colorado, in the 1980s. This is pre-MLB Rockies (and the Broncos sucked but I was a closet 49er fan by then anyway), but the City Parks & Rec adult slow pitch softball league was going strong (it still is). I was recruited by friends who worked at a computer company (an IBM spinoff, NBI=Nothing But Initials), and played for their co-rec team and also on the women's squad, the BTs (which stood for "Bodacious Ta-Tas" but everybody mistakenly called us the "Bits"). A second co-rec squad I joined was initially sponsored by Art Hardware, but later we all chipped in to finance ourselves and our captain designed a name and logo for us that reflected our shared interests: baseball and drinking.

The Intoxicators were, at the time, among the more notorious teams in Boulder co-rec softball. We were energetic, competitive, and had more fun than anybody else in the league, both on the field and off. In no universe was I ever a great softball player, but I enjoyed the heck out of playing with these guys. I made many good friends, developed some skills, and experienced the sheer pleasure of playing the game. Baseball in Boulder could be a climatic adventure: we played spring, summer and fall leagues, and any game could include hot sun, blizzards, hail, and sometimes all three. The ballparks at the eastern edge of the city had a sweeping view of storms heading in from Nebraska, and just before midnight one summer night, an Intoxicator win imminent, I was in left center debating with my fellow outfielders whether we were in greater risk of being electrocuted than the guy at the plate holding a metal bat, when … BOOM! A bolt of lightning struck the backstop. The ump wanted to quit right then and there, but we only needed one more out and begged to finish the inning. Another pitch, and BOOM! another lightning bolt hit the backstop and this time we were all willing to call it a night. We did win, and headed to a bar to celebrate our survival (and the victory, of course) with margaritas.

The Intoxicators were, at the time, among the more notorious teams in Boulder co-rec softball. We were energetic, competitive, and had more fun than anybody else in the league, both on the field and off. In no universe was I ever a great softball player, but I enjoyed the heck out of playing with these guys. I made many good friends, developed some skills, and experienced the sheer pleasure of playing the game. Baseball in Boulder could be a climatic adventure: we played spring, summer and fall leagues, and any game could include hot sun, blizzards, hail, and sometimes all three. The ballparks at the eastern edge of the city had a sweeping view of storms heading in from Nebraska, and just before midnight one summer night, an Intoxicator win imminent, I was in left center debating with my fellow outfielders whether we were in greater risk of being electrocuted than the guy at the plate holding a metal bat, when … BOOM! A bolt of lightning struck the backstop. The ump wanted to quit right then and there, but we only needed one more out and begged to finish the inning. Another pitch, and BOOM! another lightning bolt hit the backstop and this time we were all willing to call it a night. We did win, and headed to a bar to celebrate our survival (and the victory, of course) with margaritas.

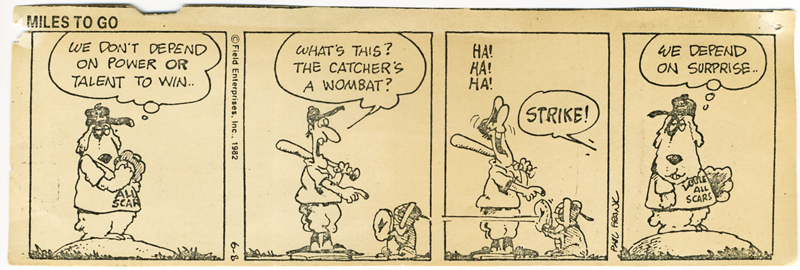

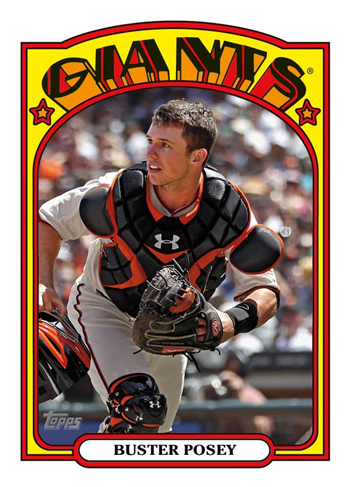

The satisfaction of snagging a fly ball in deep right field is something to be experienced, but what I really loved was catching. Compared to major league baseball, the position was pretty low key (no tools of ignorance, slides into home plate, or base stealing), but the pitcher-catcher dynamic was just as critical. The most important thing a catcher does is to keep the pitcher focused and comfortable, and sometimes distractions are the best way to accomplish that. That hilarious scene in Bull Durham where the entire team comes to the mound to discuss voodoo curses and wedding presents? Our mound conferences were kinda like that. Our best pitcher Susan and I made a killer southpaw duo, until they ruled that a battery had to be co-ed, and I could only catch for the guys. No matter: we still rocked the rec league and ruled the post-game drinking holes. My softball career ended when I moved to the West Coast and got too busy with work commutes to join another team. On the plus side, San Francisco has the most beautiful major league baseball park in the country, and the hotly talented Giants team, the fan-receptive organization, and the all-encompassing city support base (City Hall glowing orange and black last October!) make being a Giants fan an incredible experience.

… But you never forget catching, and my adventures with the Intoxicators makes me especially appreciative of the more intangible awesomeness qualities of Buster Posey behind the plate at AT&T Park. Is it baseball season yet?

Eleanor Farrell

Former Catcher and SF Giants Fan